Solaris Resources (TSX: SLS) Hits New 26-Month High

On June 12th, NIA sent out an alert saying, "At some point in the not-too-distant…

Horrible Tragedy This Morning

There was a horrible tragedy this morning. Diogo Jota the superstar football player who had…

Augusta Gold (TSX: G) Gains by 5.38% to $1.37 Per Share

Augusta Gold (TSX: G) gained by 5.38% today to $1.37 per share and has the…

NIA Never Exaggerates We Speak Truth

When we say Contango ORE (CTGO) had the highest free cash flow per share last…

First Mining (TSX: FF) Gains by 5.41% to $0.195 Per Share

First Mining Gold (TSX: FF) gained by 5.41% today to $0.195 per share and its…

What a Huge Day for BYON and CTGO

Yesterday morning, NIA sent out an alert saying, "Look for Beyond (BYON) to bounce to…

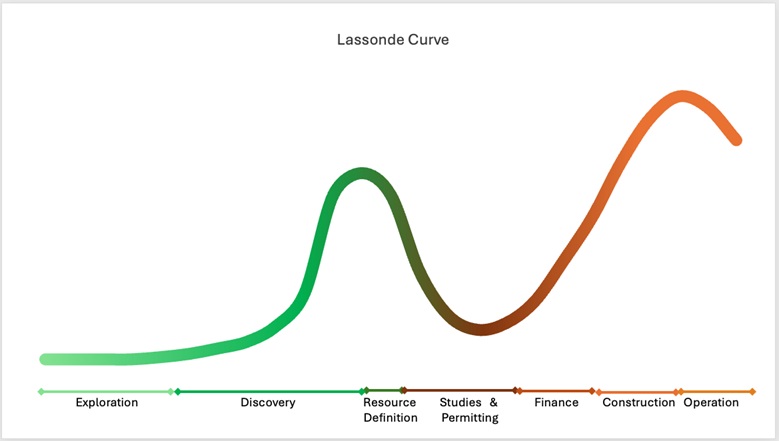

Augusta Gold (TSX: G) and First Mining (TSX: FF) Perfectly Positioned on Lassonde Curve

When you see the gains Augusta Gold (TSX: G) is about to make in the…

Augusta Gold (TSX: G) Fair Value: $7.20 Per Share

Canadian markets were closed today for a holiday but will reopen tomorrow. From the date…

Look for Beyond (BYON) Bounce to $8-$10 Per Share

Look for Beyond (BYON) to bounce to $8-$10 per share. It is very high risk…

Contango ORE (CTGO) Bouncing Strongly Since Our Alert 24 Hours Ago

Contango ORE (CTGO) is bouncing strongly since our alert 24 hours ago at $18.82 per…